We have in the past examined the origins of various numbering systems in football. The association variety is of course the main focus of this blog, but there’s no harm in looking at other codes from time to time. Today, the Rugby World Cup final takes place between New Zealand and Australia at Twickenham and so we felt it appropriate to examine how the shirt markings in that sport came to be settled on. There’s more to the story than you might think, too, and we are thankful to the Rugby Football History site and rugby historian extraordinaire John Griffiths for their help in assisting us. You might also like our sister site, International Rugby Shirts, which features all of the kits worn at the Rugby World Cup from 1987-2015.

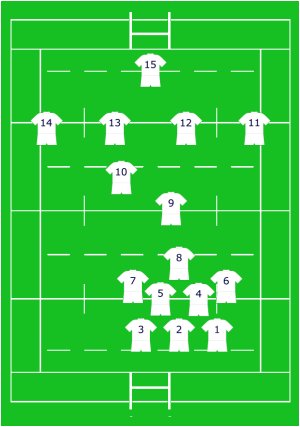

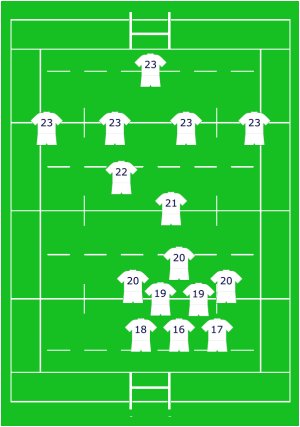

Let’s start by first having a look at the layout of a modern rugby union team:

For the uninitiated, the top seven players are the backs. Number 15 is the full-back, 14 and 11 the wingers, 13 and 12 centres, 10 the out-half and 9 the scrum-half. The remaining eight are the forwards, who contest scrums. Number 1 is the loosehead prop, 2 is the hooker and 3 is the tighthead prop (he has players packing down either side of him while 1 only has an opponent to his right), 4 and 5 are the locks, 6 and 7 flankers and the number 8 is…the number 8.

Effectively, it’s the opposite philosophy of a 2-3-5 football team from the 1930s, with the backs wearing higher numbers and the ascension going from right to left. The numbering is fairly rigid, too – the system has been laid down in law since 1967 and, apart from some instances of the switching of the wingers (11 and 14) and the flankers (6 and 7), every team follows it.

Before the decision was taken to standardise things in ’67, there was a lot of autonomy given to sides to operate as they saw fit. Part of the reason for the freedom could stem from the original motivation of numbering in the 1890s in Australia and New Zealand. At the time, there was a busy cottage industry in the production of counterfeit match programmes and so, to encourage patrons to purchase the ‘official’ versions, players were assigned numbers.

The Wales-England game in Cardiff in 1922 was the first time that both teams in a Five Nations Championship game were numbered. Ireland and France followed, but, apart from a brief dalliance, Scotland held out. When King George V gently enquired of SFU (now SRU) President James Aikman Smith as to why the Scots were unnumbered, he was gruffly informed that it was a rugby match and a not a cattle sale. Most sides numbered numbered the full-back 1 or 15 and followed in a linear fashion, but John Griffiths points out that there were occasionally inconsistencies:

In the 1938 Calcutta Cup match at Twickenham, for instance, the Scottish fly-half and scrum-half were numbered one and two; the full-back wore number 11 and the left-wing number 15. All totally illogical.

For a while, Wales opted not to field a number 13 and also had lettered, rather than numbered, shirts during the 1930s and 40s (see below for more). Another side to become associated with a lack of a 13 were Bath. In 1920, one of their players, Clifford Walwin, had sustained an injury on the pitch while wearing the number and subsequently died. Until the mandating of 1-15 by the RFU in the late 1990s, Bath’s centres were 12 and 14, the right winger 15 and the full-back 16. Richmond operated a similar system.

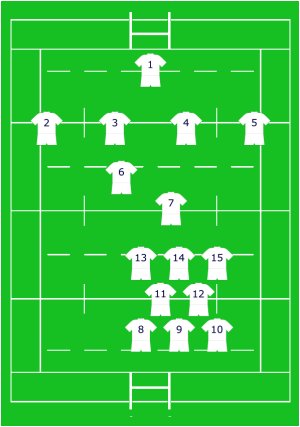

By the late 1950s, France and Ireland used a system similar to what we’re used to now. However, scrums packed differently in those days, with the flankers driving the second rows and the player between them ‘locking’ it, meaning he was generally known as the lock forward. Their forwards were numbered thus:

England, Scotland and Wales used the system seen below, beginning with 1 at full-back but starting the numbering of the forwards with the props rather than continuing from the scrum-half (7) to the lock forward. To this day, many match reports or team listings will go from 15-9 and then 1-8. Rugby league, which is 13-a-side, still uses a system like this too.

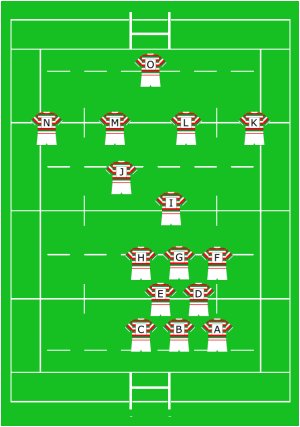

Scrummaging was changing, however. The traditional 3-2-3 was giving way to a 3-4-1 or 3-2-2-1, a new system developed in South Africa, where the lock forward was referred to as the “eighthman”. In New Zealand, that player was called the number 8 and they made the step to have him wear the same, switching around the numbering of the forwards:

It was for South Africa’s tour of the Northern Hemisphere in 1960/61 that the rest of the Five Nations countries fell in with the French/Irish numbering, and then six years later it was written into International Rugby Board law. John Griffiths relates that it wasn’t plain sailing, though:

The Springboks immediately misinterpreted this. Look at the 1968 and 1974 Bok jerseys in the Tests against the Lions – they numbered their wings before their centres. Thus 11 was left wing but 12 right wing; then 13 was left centre with 14 as the other centre!

South Africa also went against the grain in the back row of the scrum. Numbers 6 and 7 were referred to as the left and right flankers respectively when the numbering was standardised. Nowadays 6 is the blindside flanker and 7 is the openside, except in South Africa, where the opposite pertains.

There are occasionally other exceptions, like Australia’s David Campese retaining 11 when he switched to the right wing later in his career and both Brian O’Driscoll (Ireland) and Will Greenwood (England) wearing 13 when playing at inside centre despite it being the number for the outside centre.

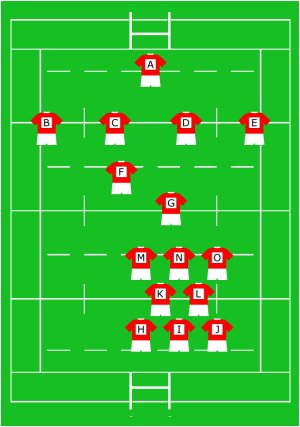

Lettering of shirts was practised by New Zealand when they first met South Africa in 1921, but Wales were the country which became most associated with it. The pattern was the same as the system which had 1 as full-back:

By the 1950s, Wales had reverted to numbers but Bristol maintained the same system until being forced to change when the RFU issed the edict instructing everyone to use the more common style. Another club which had letters until that change were Leicester. Their lettering was along the lines of the modern numbering, with the loosehead prop wearing A and the full-back O. One difference was that the number 8 wore G (the seventh letter) and the openside flanker was H.

In 2010, Leicester resurrected lettering for games against touring sides. In addition, for all games the players’ shirts carry a letter above the club crest, corresponding to the number on their backs.

Finally, it’s interesting to note that replacements in rugby union also follow a numbering pattern. Originally, the numbering began with backs. A previous article by John Griffiths lays out the way this changed:

Given that starting fifteens were numbered upwards from front-row to fullback, the logical step of similarly numbering replacements upwards from 16 to 22 in Tests from front-row to the backs was taken by Scotland, Italy, Ireland, Wales and France at the start of the 2000 Six Nations. England soon fell into line and Romania, Argentina and South Africa did so for their June Tests the same year.

Australia and New Zealand finally followed the convention of numbering replacements from the front-row cover (16 and 17) upwards for the autumn Tests in 2000 (when Wales, curiously, reverted to the old convention of labelling the back reserves from 16 upwards for their games with Samoa and the United States yet numbered from 16 upwards from the front-row reserves for their final match of 2000, against South Africa). Since then Test teams have (almost) universally numbered their replacements along the same lines as their starting fifteens: lowest number upwards corresponding with the front-row through to the backs.

Nowadays, to ensure safe scrummaging, teams in top-class rugby must carry replacements for each player in the front row. (an oddity is that 16 is often the reserve hooker rather than following the pattern of the first 15). It gives a top-heavy look to the bench if we examine the positions covered by each replacement, with number 23 required to be a versatile back, though it’s often the case that 22 can play there too: